By Kirsten Naomi Rogers Chapman and Ben Cronkright

After three months as the school improvement team lead for South Lake High School, Louisa has hit a brick wall. Her team is meeting consistently, collecting and analyzing data on student progress, implementing changes to classroom practice, and generally getting along, but Louisa feels like they’re going in circles—and the data on student learning outcomes shows very little progress. When she mentions this stagnation, her teammates listen, but ultimately dismiss her concerns. On the way out of a meeting, Abel, one of her biggest supporters, tries to reassure her. “Sometimes, that’s just the way things are,” he says.

Louisa is facing a common issue within teams assembling for continuous improvement: getting stuck. While there’s no single cure for getting unstuck, teams that can move past lulls of stagnation and continue to advance progress toward their goals tend to foster strong team learning environments.

What makes a strong learning environment for your school improvement team to excel? It’s a combination of promoting a psychologically safe environment while engaging in double-loop learning.

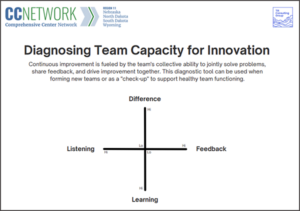

Part of the work being done by a partnership of the Region 11 Comprehensive Center, the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, and North Dakota Regional Education Association is supporting North Dakota public schools to develop psychological safety and double-loop learning to empower teams of teachers, leaders, and community members to identify and solve challenges in a disciplined and evidence-based way. For example, The North Dakota School Renewal Handbook is a problem-solving mechanism to help any school leader support school improvement teams and includes practical tools like Diagnosing Team Capacity for Innovation.

Part of the work being done by a partnership of the Region 11 Comprehensive Center, the North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, and North Dakota Regional Education Association is supporting North Dakota public schools to develop psychological safety and double-loop learning to empower teams of teachers, leaders, and community members to identify and solve challenges in a disciplined and evidence-based way. For example, The North Dakota School Renewal Handbook is a problem-solving mechanism to help any school leader support school improvement teams and includes practical tools like Diagnosing Team Capacity for Innovation.

Promoting Psychological Safety to Promote Collective Efficacy

According to Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson, a psychologically safe space is “one where people are not full of fear and not trying to cover their tracks to avoid being embarrassed or punished.” In addition, schools with high levels of psychological safety were more likely to “promote collective learning and change, ultimately leading to improved organizational performance,” according to a recent study by Jennie Weiner, Chantal Francois, Corrie Stone-Johnson, and Joshua Childs. Those who have authority over others’ work—such as the principal or team leader—are primarily responsible for establishing a psychologically safe space, which can then be nurtured and maintained by the entire team.

Edmondson cites three simple key behaviors team leaders can take to do this:

- Set the stage. Explain the nature of the team’s work and why everyone’s input is not just valuable, but also necessary to the team’s success.

- Invite input. Ask for team members’ thoughts proactively and directly.

- Respond appreciatively. After team members provide their perspectives, which you have invited them to share, recognize their contribution. This doesn’t mean you have to agree or express excitement about their point of view, but rather that you are encouraging team members to speak up.

By modeling these behaviors, the team leader makes the behaviors part of the accepted way of working together.

Engaging in Double-Loop Learning

Perhaps the simplest way to explain single-loop vs. double-loop learning is to imagine a thermostat. Let’s say you set your thermostat to 68 degrees Fahrenheit, then walk away, trusting it will adjust accordingly to any changes in temperature. If the temperature rises above 68 degrees, the thermostat will turn on cool air. If it drops below 68 degrees, it will turn on warm air. The thermostat will consider—and only consider—the single piece of information you have deemed important (the actual temperature) to guide its behaviors in pursuit of its goal (maintain 68 degrees). What the thermostat isn’t designed to do is to consider whether it should be set to a specific temperature or if it is placed in the most optimal location. That type of thinking is left to you—the person managing the thermostat.

Just as the thermostat uses temperature to determine whether it should heat or cool, single-loop learning is the process of using information to guide behavior. Within your school team’s continuous improvement efforts, you set a goal for student growth and achievement and—just like the thermostat—adjust your behaviors to meet that goal.

Double-loop learning involves stepping back from the process of disciplined inquiry (Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles) and examining the learning environment as a whole. When teams engage in double-loop learning, they examine and evaluate the underlying assumptions that are driving their behaviors. Teams that successfully engage in both single-loop and double-loop behaviors regularly:

- reflect on what happens,

- reflect on how the team responds to what happens, and

- reflect on what is driving the team’s response to what happens.

Let’s return to Louisa.

She realizes that the team spends plenty of time talking about what they do, but practically no time discussing what is driving their behavior. For example, Louisa noticed the team is resistant to collaboration, preferring to complete tasks and implement interventions independently. Louisa has a hunch that students might benefit more if the team implemented some interventions together. Louisa decides to share her thoughts at the next team meeting.

“I’ve been thinking about how we approach implementing our interventions,” Louisa begins. “We seem to work on them separately, but I think we’d see more progress if we’d pair up and work collaboratively on some of these. What do you think is getting in the way of us teaming up in this way?”

A lively discussion follows. By the end of the meeting, the team uncovers an assumption: some team members are concerned that collaborating will force them to give up their autonomy in their classroom (and, honestly, some team members don’t like the way others run their classroom). They don’t want to risk giving up that control.

Once that assumption is surfaced, Louisa breathes a deep sigh of relief. There is still plenty of work to be done in further examining and testing that assumption in support of the collective growth of the team, but they have taken a crucial step forward by identifying a shared belief that has been driving the team’s behavior. Without creating and engaging in this space for learning, the team was likely to continue to go around in circles.

As the Weiner et al. study mentioned earlier notes, “Leaders must create conditions [so that] members can examine underlying assumptions regarding current practice and facilitate opportunities for new ways of thinking and doing.” Successfully creating and maintaining these conditions can help develop psychological safety necessary for teams of teachers, leaders, and community members to develop winning solutions together.

Related Resources to Get Started

Psychological Safety

- Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace This podcast features Amy Edmondson, who explains psychological safety and how to promote it within teams.

- Make Your Employees Feel Psychologically Safe This article features Amy Edmondson and explains the important role of leaders in establishing and nurturing a psychologically safe environment.

Double-Loop Learning

- Diagnosing Team Capacity for Innovation This free, downloadable team activity can help diagnose your team’s capacity for learning and innovation.

Kirsten Naomi Rogers Chapman, Ph.D, is project consultant for the R11CC, currently serves as the vice president of systems change and innovation at United Way of Greenville County and is the founder and principal of Tilt Consulting Group. She is a lifelong learner and former educator from Clarksville, Tennessee.

Ben Cronkright, M.A., is a senior consultant at McREL and currently leads partnerships engaged in high-leverage problem solving within the Regional Education Laboratory—Pacific Region as well as the Region 11 Comprehensive Center. Ben has provided research-based insights in understandable and meaningful ways on a variety of topics, including college and career readiness, family and community engagement, school leadership, teacher effectiveness, and systems improvement.